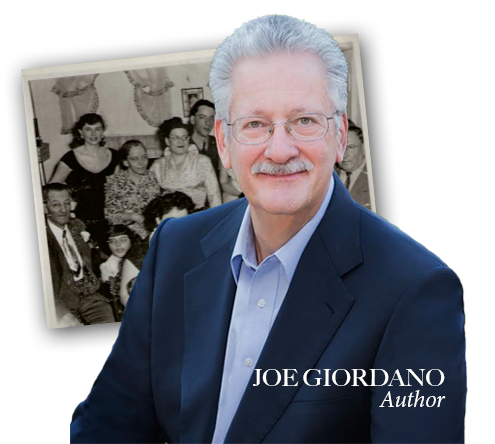

Wedding photo of my Uncle Ralph and Aunt Jeanette just after he left military service. Taken in 1952 at my Grandparents’ tiny apartment in Brooklyn. My father is on the right with a mustache, my mother between Uncle Ralph and Grandma Philomena. Grandpa Anthony is far left. The author, at three-years-old, is pictured in the lower right.

Wedding photo of my Uncle Ralph and Aunt Jeanette just after he left military service. Taken in 1952 at my Grandparents’ tiny apartment in Brooklyn. My father is on the right with a mustache, my mother between Uncle Ralph and Grandma Philomena. Grandpa Anthony is far left. The author, at three-years-old, is pictured in the lower right.

As with the character, Guido Basso in Birds of Passage, both my grandfathers were ragmen. Their labor was dirty and backbreaking, but they were their own padrone.

My father was the last immigrant in my family. He acquired just a seventh-grade education before he set out to work. Unemployed for a long period during the Great Depression, he found a job in a warehouse. Working rapidly to impress the boss, he reached up for a box atop which a vase had been left. The glass knickknack slipped and shattered onto the concrete floor. My father was fired on the spot. Not deterred, he started his own business. My mother was one of five daughters employed at home doing piece work so her family could earn enough money to leave the tenement. Eventually her family purchased a home in Brooklyn.

Despite the prejudice Italians experienced, they never saw themselves as victims. They were too busy working, trying to make a better life for themselves and their families. When I was growing up, if my father and I passed a man doing hard manual labor, my father would say to me, “See that? Go to school.” My success was built upon the foundation given to me by my parents. Many Italian-Americans stand upon the shoulders of those intrepid enough to try and make a better life in a new country. Birds of Passage is not a biography about my family, but I’m old enough to have known people who were born in the nineteenth-century. In the novel I tried to capture how Italian immigrants of past generations thought and acted.

Wedding photo of my Uncle Ralph and Aunt Jeanette just after he left military service. Taken in 1952 at my Grandparents’ tiny apartment in Brooklyn. My father is on the right with a mustache, my mother between Uncle Ralph and Grandma Philomena. Grandpa Anthony is far left. The author, at three-years-old, is pictured in the lower right.

Wedding photo of my Uncle Ralph and Aunt Jeanette just after he left military service. Taken in 1952 at my Grandparents’ tiny apartment in Brooklyn. My father is on the right with a mustache, my mother between Uncle Ralph and Grandma Philomena. Grandpa Anthony is far left. The author, at three-years-old, is pictured in the lower right.